The 2026 national budget marked a historic policy shift in Sri Lanka’s development trajectory. For the first time, the President allocated a dedicated budget line—LKR 100 million—for the establishment and advancement of the Blue Economy sector. Although Sustainable Development Goal 14- Life below water was introduced globally by the United Nations in 2015, no Sri Lankan government has previously presented such a substantial or structured investment toward a holistic “Blue Economy” framework which has been aligned with SDG no 14. This allocation represents both an opportunity and an immediate challenge: determining how to effectively utilize these funds within a fragmented institutional landscape, especially since the budget proposal originated from the Presidential Secretariat, not the Ministry of Fisheries.

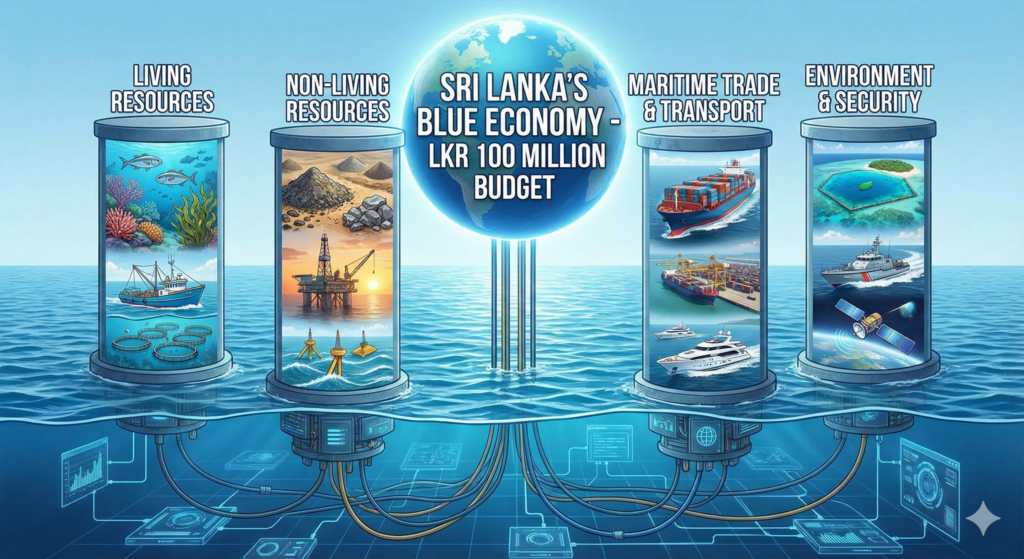

A recent article in Daily News referred to a “Blue Economy Foundation laid” with the Aqua Planet program. However, the term “foundation” carries problematic international connotations and does not align with the strategic requirements or institutional positioning needed for a national Blue Economy initiative. The funds allocated must be utilized under a framework grounded in four core pillars that represent the full spectrum of ocean-based development:

1. Extraction of Living Resources

2. Extraction of Non-Living Resources

3. Maritime Trade and Transport

4. Marine Environment Protection and Maritime Security

These four pillars collectively encompass every ocean-based opportunity available to Sri Lanka. If implemented coherently, they can serve as the vehicle to accelerate national economic growth and elevate Sri Lanka’s position in the global maritime system. The sections below provide an in-depth analysis of each pillar, the governance gaps that hinder progress, and the strategic interventions required.

1. Extraction of Living Resources

This pillar includes fisheries, corals, seaweeds, mari culture, and related subsectors. At present, Sri Lanka lacks a unified and credible policy framework for Fisheries. Existing policies are fragmented, outdated, and inadequate to address modern market demands or sustainability obligations. Before any expansion takes place, the country needs three critical policy foundations:

* A coherent national security policy

* A strong and proactive foreign policy

* A dedicated education policy

Harnessing living marine resources is not merely a fisheries issue but an international economic opportunity. Sri Lanka cannot compete or collaborate globally without a robust foreign policy. However, due to security-oriented limitations, these areas have not been adequately developed.

The budget’s emphasis on “research” is the most concerning gap. Sri Lanka does not have long periods available for basic research, nor does it need to reinvent knowledge that the world has already advanced. The priority should be technology integration, not traditional research. Bringing global technology into Sri Lanka and building a strategy around it is the only practical path forward.

A single comprehensive Fisheries Policy is required—one under which all Blue Economy activities also are aligned, instead of producing numerous individual policies.

During a visit to the Presidential Secretariat, it was observed that a separate “Mari Culture Policy” was being drafted. This approach is misguided. What Sri Lanka needs first is a Mari Culture Strategy, followed by an action plan. This requires foundational information the country currently lacks:

* How many vessels are available in NAQDA for mari culture activities?

* Does the NAQDA have sufficient skilled personnel?

* Where can cage culture be implemented?

* Which coastal zones are suited for seaweed cultivation?

* Where are the optimal water compositions for such industries?

* How do we scientifically explore northern resources such as lobsters ,sea cucumbers and other hidden biodiversity?

Without these datasets, no policy or investment can produce meaningful outcomes.

To avoid fragmentation, funds should be managed through a Special Task Force on Blue Economy , operating from the Presidential Secretariat, ensuring inter-ministerial coordination. Otherwise, ministries will spend funds on isolated events with no long-term value. A specialized, empowered team must also support Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) proposals and represent Sri Lanka at high-value global Blue Economy forums.

A steering committee comprising Minister Anil Jayantha, Deputy Minister Chathuranga Abeysinghe, and the Secretary to the Ministry of Finance, or alternatively the already Cabinet-approved Center for Ocean Resources Analysis Think Tank CENORA , should oversee strategic implementation.

2. Extraction of Non-Living Resources

Non-living marine resources include salt, ocean minerals, ilmenite deposits in Pulmudai, thorium, titanium, uranium, and potentially other mineral reserves in the northern sea and Mannar Basin. Discovering and commercializing these resources could transform Sri Lanka’s economy. However, meaningful geological exploration cannot be undertaken with an allocation of just LKR 100 million.

These resources must be studied and marketed globally. Exploration should not be limited to the Geological Survey and Mines Bureau (GSMB); it requires international partnerships, marine geophysics, and modern seismic technologies.

Renewable ocean energy—particularly wave energy,off shore wind mills—should also fall under this pillar. The long-term contribution of marine renewable energy directly aligns with the sustainable economic aspirations of the Blue Economy.

3. Maritime Trade, Transport, and Marine Tourism

Shipping is at the core of this sector. The National Hydrographic Office plays a vital role by producing Nautical charts—an untapped source of foreign revenue. Chart production, data dissemination, and maritime navigational services are potential income generators if properly developed.

Sri Lanka has opportunities in boat building, ship building, and particularly yacht building. However, a yacht culture must be cultivated before promoting mega-yacht tourism.The success of Sri Lanka’s commercial whale-watching industry is a prime example. Despite emerging during the most violent period of civil conflict—when tourism seemed impossible—the industry grew because Sri Lankans themselves created the culture first. This same principle must apply to yacht tourism.

Sri Lanka can:

* Host yacht races

* Arrange yacht passages near Port City

* Attract regional yachting communities

* Promote ocean-based sports tourism (the only practical sports platform for Sri Lanka)

Sports like football and the Olympics are unrealistic for the country like ours . Instead, marine sports offer a competitive niche.

4. Marine Environment Protection and Maritime Security

MEPA operates under its own ministry, but MEPA alone cannot maintain ocean sustainability. Nor can the Ministry of Fisheries manage marine environmental protection effectively. The two institutions must collaborate rather than operate separately.

Maritime security does not generate direct revenue, but it is the backbone of Sri Lanka’s strategic positioning. The country’s Sea Lines of Communication (SLOCs)—especially those originating from the sea routes in southern SL—must be protected through international defense cooperation.

Historical controversies over agreements such as ACSA and SOFA overshadowed their strategic value. The U.S. naval ship referenced in the SOFA discussions is now arriving under support arrangements—not accidental occurrences but deliberate security frameworks.

Sri Lanka cannot rely solely on the Navy for maritime security; policy guidance and international cooperation are essential.

The former Indian Navy Commander famously stated that India will become a major economic power due to its maritime strengths. By 2050 and Indian Navy should support its economic growth, India is expected to rise to the third-largest economy in the world. Their strategic planning, governance systems, and technological excellence—especially in software engineering—are already transforming global markets.

Sri Lanka lacks similar systems, despite claiming geopolitical importance in the Indian Ocean. Being the “pearl of the Indian Ocean” has no value unless the country translates its position into actionable strategy.

The allocation of LKR 100 million to the Blue Economy is an important symbolic beginning. However, unless Sri Lanka adopts a practical, technologically driven, globally coordinated, and institutionally unified approach, this investment risks being wasted on events and fragmented activities.

Sri Lanka must develop exportable Blue Economy projects, present them on international platforms, attract global investors, and establish a governance structure capable of driving real transformation.

If the President and the responsible institutions take these recommendations seriously and implement them effectively, the national Blue Economy initiative can become one of the most successful development programs in Sri Lanka’s modern history.Even the opposition too can drive these proposals with their capacity for the betterment of 22 million people of this beautiful Island Nation .

Ayesh Indranath Ranawaka

Executive Director INORA .

Leave a Reply