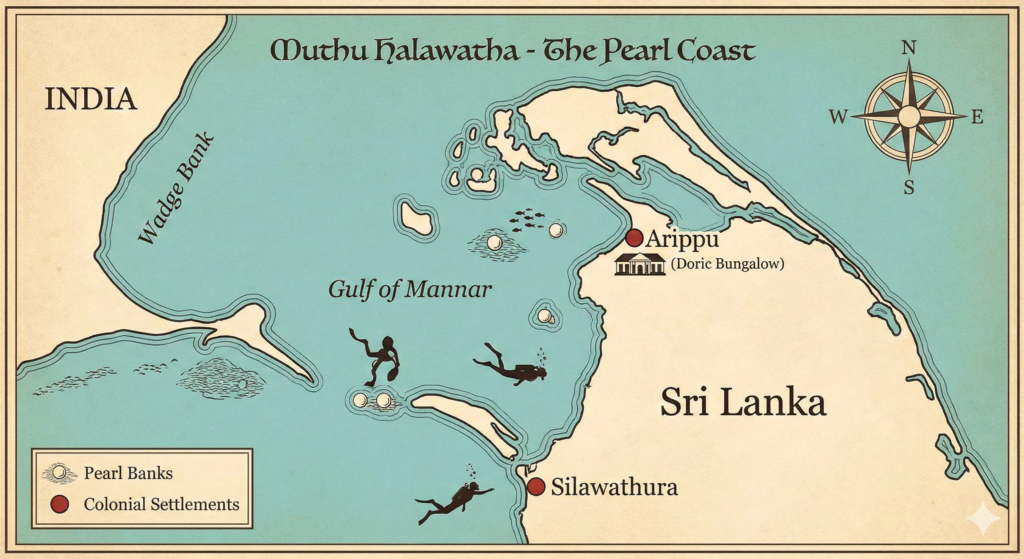

The sea off Sri Lanka’s northwestern coast does not merely hold water; it holds ghosts. For two thousand years, this stretch, known in Sinhala as “Muthu Halawatha” —the Pearl Coast—was the engine of empires, the source of the epithet “Pearl of the Indian Ocean.” It was here, in the Gulf of Mannar on the continental shelf, that specialized pearl banks teemed with the Indian Pearl Oyster (Pinctada fucata). This bounty attracted the world, yet today, the oyster beds are silent, the fortune is gone, and the tangible reminders of this glorious past are crumbling into the very ocean that once provided its wealth.

One such tragic reminder stands between Arippu and Silawathura: the ruin of the Doric Bungalow. This was once the residence of the colonial governor, strategically built in Arippu to oversee the lucrative northern pearl fisheries. But the Doric Bungalow holds a deeper, more poignant story—a connection to Sri Lanka’s own tragic royalty. It was here, facing the vast ocean that guarded the pearl banks, that Kusumasana Devi, later known as Dona Kathirina, was reportedly held by the Portuguese. Her royal lineage made her a political pawn; any man who married her could claim the throne of Kandy. The fact that a place so tied to this powerful story—a nexus of colonialism, royal intrigue, and immense wealth—now stands dilapidated, a victim of sea erosion and neglect, is a sad testament to how the nation has let its history slip away.

The reason the colonists built their headquarters here was simple: immense wealth. This region, including parts of the adjacent Wadge Bank now in Indian territory, was once the world’s greatest natural source of pearls. Generations of divers risked their lives plunging into the deep to harvest the Pinctada fucata. However, this ancient industry was fragile. The pearl fishery declined dramatically due to a confluence of factors: relentless overexploitation, adverse climate issues, and the sheer demands of human activity. By the 1970s, surveys showed the pearl oyster populations were disastrously low, and the once-vibrant natural fishery disappeared entirely. Sri Lanka lost more than just a resource; it lost a cultural cornerstone, shifting its coastal focus instead to more reliable resources like edible oysters, which are today admired by tourists.

The dream of reviving the pearl trade, however, remains stubbornly alive. The current goal, championed by agencies like the National Aquatic Resources Research and Development Agency (NARA) and NAQDA, is not to resurrect the fragile natural banks, but to establish a modern, sustainable pearl culture industry to generate foreign exchange. In 2009, an ambitious project was launched in the very region of Pesalai. But this attempt immediately ran into a thicket of bureaucratic and human hurdles. Since local oyster populations were severely depleted, stock had to be sourced from places like Vietnam. This importation process required overcoming strict approvals from the biodiversity section of Wildlife, followed by a mandatory 24-hour quarantine period upon arrival—the kind of difficulties that can stall any major initiative.

More critically, a deeper problem was revealed by the very people meant to benefit: the local community. According to accounts from retired senior NAQDA officials, the failure stemmed largely from the attitudes of the community. The community, accustomed to the intermittent natural bonanza where they simply had to systematically remove vast ‘vines’ of oysters, approached the farming with what was described as “sheer laziness,” failing to maintain the beds and successfully harvest pearl-bearing oysters. This proof was stark: without consistent discipline and modern systems, the traditional approach was doomed. NARA, recognizing the challenge, has since pivoted to using GIS and satellite data to pinpoint the most suitable, environmentally harmonious sites for cultivation, moving beyond the guesswork that plagued earlier efforts.

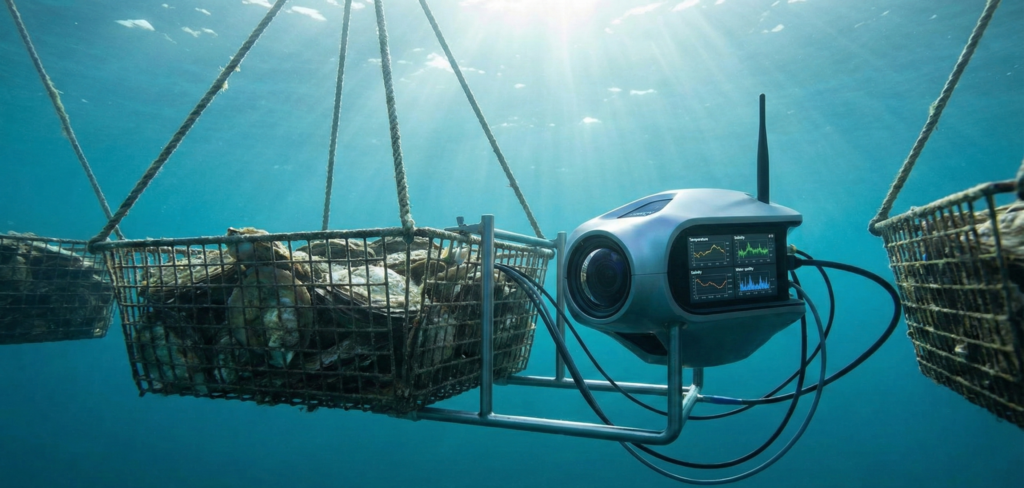

The magnificent legacy of Sri Lanka’s “Pearl of the Indian Ocean” was not lost to the sea, but to mismanagement and a failure to evolve. The past attempts at revival, hampered by bureaucracy and inconsistent community commitment, prove that a different approach is mandatory. We at “blue biz lanka” believe the time for sentimentality is over. Our vision is to use the very tools of the twenty-first century—digital monitoring, remote sensing, and advanced data analytics—to restore the island’s aquatic wealth. By leveraging technology, we can bypass the old systemic failures: deploying underwater cameras and sensor units to feed crucial, real-time environmental data via satellite into our intelligent systems. This ensures every factor critical to pearl growth—water quality, temperature, and current—is precisely controlled. The return of the pearl is possible, but only by taking the risk of human inconsistency out of the laborious process and entrusting the cultivation of our national jewel to the precise, unwavering eye of the digital world.

Ayesh Indranath Ranawaka

Executive Director

INORA

Leave a Reply